While the prospect of eating insects sounds unacceptable to many consumers, industry leaders see significant promise in their ability to help meet the need for a more sustainable supply chain and more protein.

Alexandra Kazaks, PhD, RD, a member of the nutrition division at the Institute of Food Technologists, said the entry of Tyson Foods into the insect space lends it legitimacy. The meat giant recently announced a strategic investment with startup Protix to boost insect ingredients for use in the food supply chain, specifically for use in animal feed.

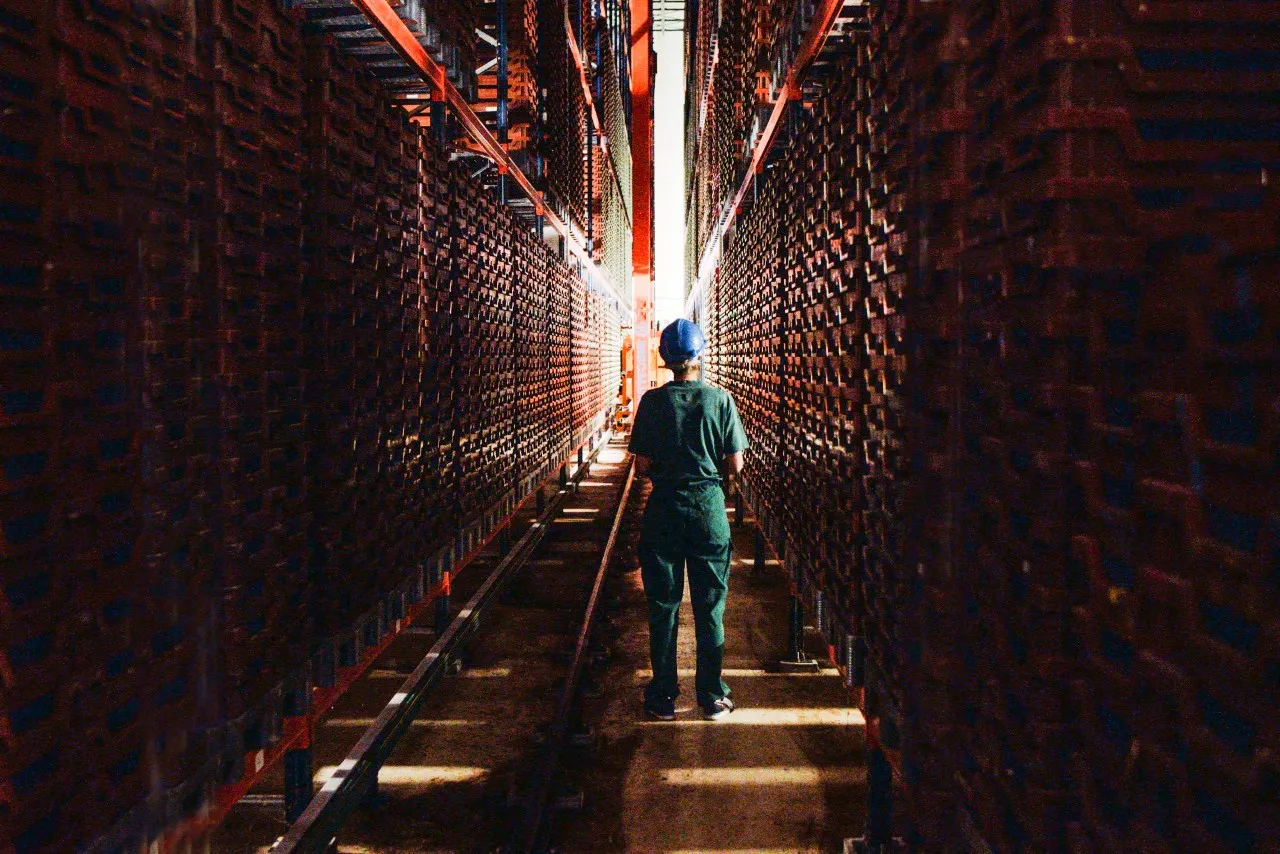

Despite Tyson not investing in insects for use in human food, Kazaks said it comes as industry players are taking the prospect of implementing bugs into the food system seriously, and scaling up production can help it meet that demand. Insect farming, she said, currently lacks the infrastructure for widespread adoption. The space can help solve costly issues, she said, including feedstock availability, disease management and environmental sustainability.

“Tyson’s interest in insect ingredients as an extension of their existing business is a clear indication of the potential this market holds,” Kazaks said.

As food and beverage companies work to overhaul their supply chains to reduce their carbon footprint over the next decade, implementing insect protein into their operations could drive down their use of resources. 8 square meters of land are needed to grow a pound of crickets, compared to 115 square meters needed for a pound of beef, producer Cricket Powder said.

According to the IFT expert, companies starting with using insects as animal feed could provide fewer barriers for entry into the space with lower costs.

“By starting with animal feed, companies can gain experience, refine their methods, and develop more efficient production processes before expanding into the potentially larger and more competitive human food market,” Kazaks said.

The promise of edible insects

While insect protein is gaining steam in the West as an ingredient, it is still met with skepticism and an “ick” factor from many as an actual food source.

Consumers who are unfamiliar with the use of insects as a protein source may take a while to be convinced, based on their associations of bugs with disease and disgust.

But as consumers increasingly seek out protein in their food and beverage items, insects provide a new frontier. Cricket flour, for example, contains between 12 and 20 grams of protein per 100-gram serving.

Kazaks said producers should tailor insect-based products by emphasizing their positive attributes, even if they don’t align with their taste and texture preferences. This could include labels explaining the nutritional benefits — such as the protein content, vitamins and minerals they contain — along with the sanitary conditions edible insects are raised in compared to conventional livestock, she said.

“To address this unfamiliarity, it would be helpful to introduce insect-based products in a way that is not intimidating and emphasizes their nutritional benefits, their potential as versatile, inconspicuous ingredients in food products,” Kazaks said.

Adventurous eaters looking for new protein sources are the most likely consumers to try new products made with insects. Future insect-based products could include dietary supplements, flavor enhancers, powders, bars and burger patties, according to Kazaks.

Similar to other alternative protein products, producers also stand to benefit from stressing how much less carbon and water it takes to produce edible insects than livestock, she said.

“As the food industry continues to evolve, insect proteins, as with plant-based and cell-based alternatives, represent a promising and sustainable alternative that deserves attention and investment,” Kazaks said.