Beginning in 2018, North American farmers and scientists started noticing an unnerving and unusual trend: Oysters were dying at alarming rates in mass mortality events.

In some cases, fisheries from British Columbia, the U.S. East Coast and Gulf of Mexico saw their farms virtually wiped out. And the trend wasn't contained to 2018, either, with mortality events making the news every summer for the last few years.

"There were farms that I visited that had 95% mortality,” said Tim Green, a professor of fisheries and aquaculture at Vancouver Island University.

Mass oyster mortalities would do more than just decimate the fishing industry — it could also hurt efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Oyster reefs can store carbon, filter water and protect surrounding habitats from erosion .

“[Oysters] filter the water, which removes a lot of phytoplankton and nutrients, so they're a good sink for nitrogen and phosphorus coming off agricultural or human wastewater that pollute the water,” Green said. “They have a really huge impact on our environment in a positive way.”

Green and his team are working on "future-proofing" the shellfish industry through new breeding programs and by encouraging growers to adopt new production techniques. But a lack of quality data, combined with limited understanding of why mass mortality events occur, could hamstring efforts to save oyster populations.

Die-offs prompt differing explanations from farmers, researchers

A new study awaiting publication as of January 2024 looks into one of the problems in getting to an answer about what's killing oysters in British Columbia: farmers and scientists haven’t always agreed on the factors causing it.

Between oyster growers and scientists, there is some agreement that factors like water temperature and pathogens such as harmful algae blooms can affect, and even kill, farmed oysters.

However, the study awaiting peer review, is poised to show that scientists and growers held differing views about the age and size of oysters susceptible to mass mortalities and the role food availability plays.

Notably, growers indicated factors not chosen by any scientists, such as rainfall, microplastics, and invasive green crabs. Meanwhile, scientists tended to cite the importance of factors like ocean acidification, while noting that growing decisions tend to have less impact.

Sahir Advani, who worked on the research while at the University of British Columbia, says that public awareness concerns are somewhat of a hurdle in finding answers. Advani used to work for a Vancouver community-supported fishery, and has heard from oyster growers who expressed concern that the research could create negative perceptions of the seafood industry among consumers.

“This research is slightly sensitive as reports of oyster mortality have impacts on the public's perceptions about consuming oysters and supporting the industry,” Advani said in an email to Agriculture Dive. “Oyster growers have personally told me that they would rather this research not be published due to the potential negative stigma that may occur.”

Fisheries have dealt with a tide of food safety issues over the years, including a norovirus outbreak in 2022 from raw B.C. oysters that prompted the government to advise consumers against eating undercooked shellfish.

Headlines like “ Norovirus outbreaks linked to B.C. oysters ,” and “ Why you may never eat raw oysters again ” permeated the web, and affected consumer opinion. British Columbia has since closed the investigation, though growers still worry that bad press — even temporarily — could have negative market impacts.

How to 'future-proof' the shellfish industry

Despite the hurdles, market predictions for oysters are promising . Looking forward, Green said he is optimistic about the industry’s future, noting some remarkable advancements in breeding and changes to production practices.

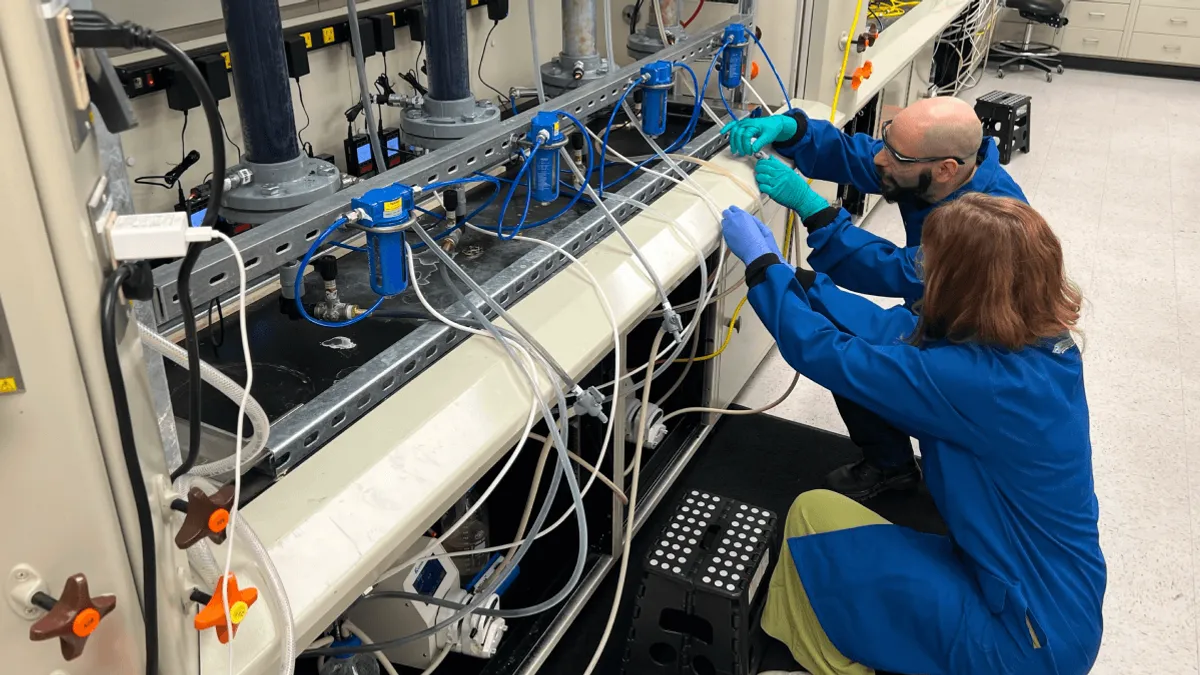

While the occasional farm still gets hit quite hard by summer mortality events, larger producers are combating the issue by changing their approach to techniques like seawater buffering , which uses chemicals to change water pH and slows ocean acidification.

Looking back to 2018, Green said it was common to see growers reporting that 4 out of every 5 oysters would die before harvest. In the last two years, that number has gone down to about 20% mortality.

“I think there's a lot more optimism in the industry around mortality than there was five years ago,” Green said.

Advani, who led the study investigating reasons behind mortality events, said Green's work is promising, though noted that more needs to be done to expand the new growing strategies to more fisheries.

“Dr. Green's observations are encouraging as they suggest that B.C. oyster growers are adapting their growing techniques to reduce the susceptibility of oysters during the warmer summer months," Advani said. "Better reporting on what adaptation strategies oyster growers are implementing would be very useful.”

Vancouver Island University researchers have also bred oysters to help them withstand potential disease or environmental irregularities . Under Green, the team is studying how to help the shellfish adapt to disease, ocean acidification, marine heatwaves and other climate issues.

"We've got all these stresses and challenges, and so we're trying to get ahead of the game by understanding how you breed an oyster to be resistant,” Green said.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Advani's title when he worked on the study. He was a researcher at the University of British Columbia. It also misrepresented Advani's comments around whether the study would be published and which growers reacted to the findings. He did not express concern about the study's publication.