What do the various dates for “best if used by,” “sell by,” expiration, freshness or other labels on food packaging mean? Not much actually. Eventually there could be a new system entirely.

This confusion and concerns around wasted food have motivated a crowd of major companies, researchers and startups to address the problem of food freshness. By using various sensor technologies, a product’s status can be known along the supply chain all the way to grocery shoppers, who hopefully won’t throw out food that’s safe to eat after they get it home.

As per the U.S. Department of Agriculture, "[t]here are no uniform or universally accepted descriptions used on food labels for open dating in the United States." Confusion around this issue likely contributes to the 38% of unused food — 80 million tons — in the U.S. each year, according to nonprofit ReFED. The Food Date Labeling Act was recently reintroduced in Congress in an attempt to address this issue, and states have also considered policy changes.

"The current standards are the ‘use by’ date that has to do with whatever the manufacturer decides to put there," said Silvana Andreescu, professor of bioanalytical chemistry and head of the biosensors lab at Clarkson University. "It doesn't take into account storage conditions and transportation conditions, so it is not related necessarily with the quality and the value of the food at the time of use."

Best for what?

The condition of the majority of food products as they travel along supply chains is unknown because there's no quality monitoring, apart from perhaps a visual inspection at the grocery store, said J.-C. Chiao, professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at Southern Methodist University. "You don't know what happened to the product," he said.

There are a variety of approaches being developed and marketed using inks, pH sensors, hydrogels and other technologies. Andreescu and Chiao have both been involved in projects to create freshness sensors.

Andreescu's group developed a sensor that changes color when the food begins to degrade. Fish and meat both produce more hypoxanthine as they begin to spoil. The biosensors in their paper label react to that increase and trigger a color change. The label itself is placed inside packaging on a membrane so it's not in direct contact with the food.

Chiao supervised SMU doctoral student Khengdauliu Chawang, who developed a low-cost pH sensor that detects the level of hydrogen ions in the food product. The ions affect the pH levels and that info is relayed to servers along the supply chain using radiofrequency identification, or RFID, technology. It's designed to be easily mass produced and, at 2 millimeters by 10 millimeters, is very small.

Chawang, who is from the Nagaland region in northeastern India, was motivated to address freshness for personal reasons. "Food waste is such a problem in the community that I come from," she said. "There are consequences for that."

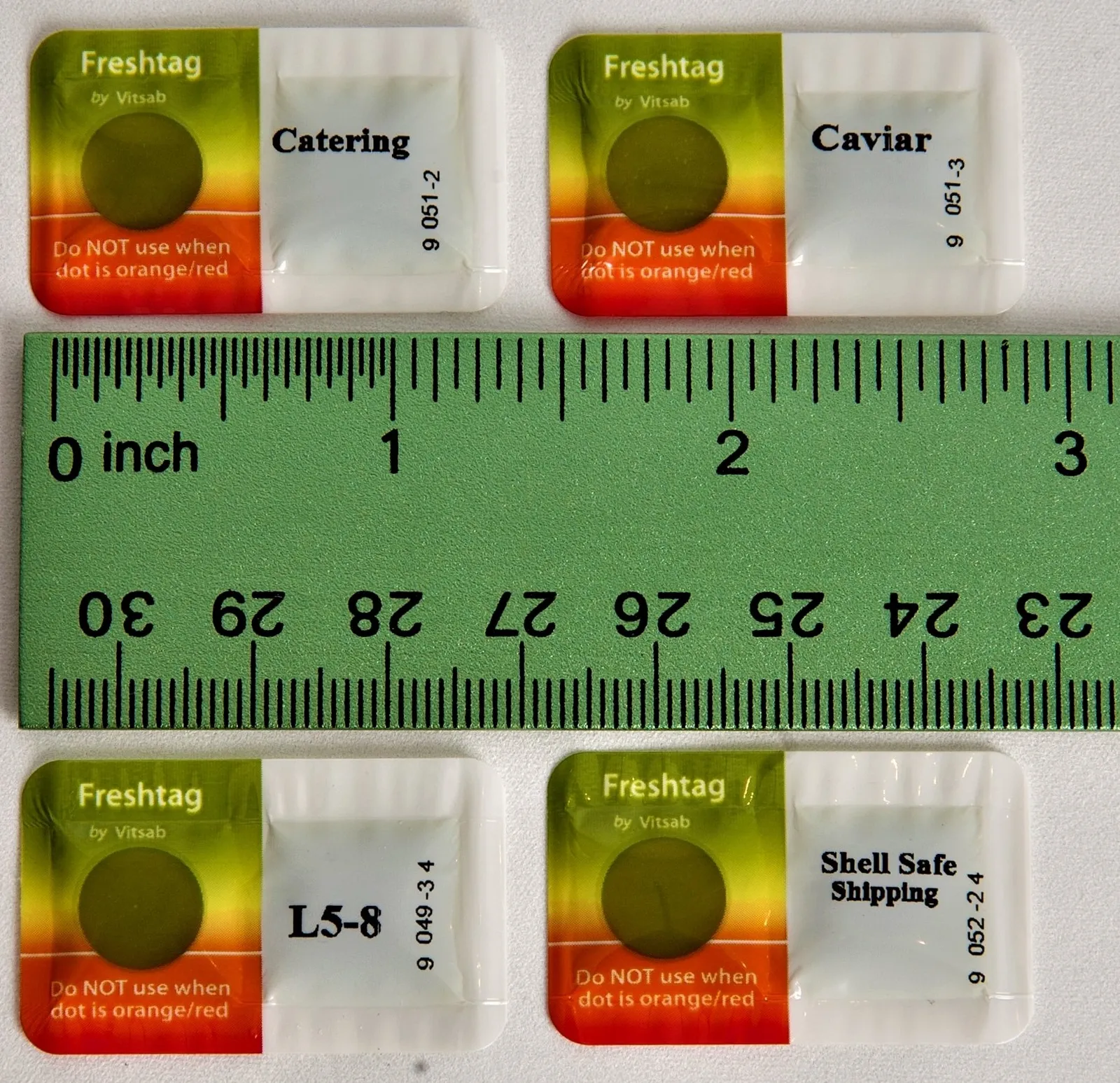

Another product that uses color coding is the Freshtag from Swedish and U.S.-based research and development company Vitsab. The Freshtag is a freshness indicator that changes like a stoplight from green to red, using food-safe adhesive to attach to a label. It's calibrated to specific food product temperature regulations, explained President Jeff Desrosiers. The company is also working on an ink-based technology that would be embedded in a package's barcode. The barcode would fade according to the temperature profile and then be unsellable when it was past edibility.

"If something is well handled, it's good well beyond that [‘use by’ or expiration] date," Desrosiers said. "But if it's abused, it's not even good until that date. So the industry has to come up with something."

This field has also seen engagement from companies around the world. For example, Sweden's Innoscentia offers a label that attaches to plastic film of a meat package. When the meat degrades, it releases volatile organic compounds which react with the label's ink, causing it to change color.

Nantotechnology is also being explored for freshness applications, said Andreescu, who's done work on this herself by looking silver nanoparticles used as antimicrobials for packaging. In a sign of this field gaining traction there is a USDA nanotechnology research program. But there's also the issue of USDA and Food and Drug Administration rules for nanotech products that come in contact with foods, Andreescu said. "I think for regulation of these new technologies, there needs to be clarity," she said.

Sensor scaling

While there’s no shortage of ideas, getting them to scale — and market dominance — will take acceptance and time.

There's resistance on the part of manufacturers and food producers to change their packaging lines to accommodate these new technologies, experts say. Angel Veza, senior manager of capital, innovation and engagement at ReFED, said it can cost a lot for manufacturers to change seemingly small aspects of their packaging.

For example, Mimica in the U.K. developed a packaging insert containing a temperature-sensitive hydrogel that changes as the product ages. When used inside a beverage bottle cap, the cap itself deforms from smooth to bumpy, indicating when the product has spoiled.

"That is going to be a big challenge for a lot of these types of companies that are trying to integrate into existing packaging, whether it's just even being on the label or changing a cap, and that can have a lot of costs associated to it," Veza said.

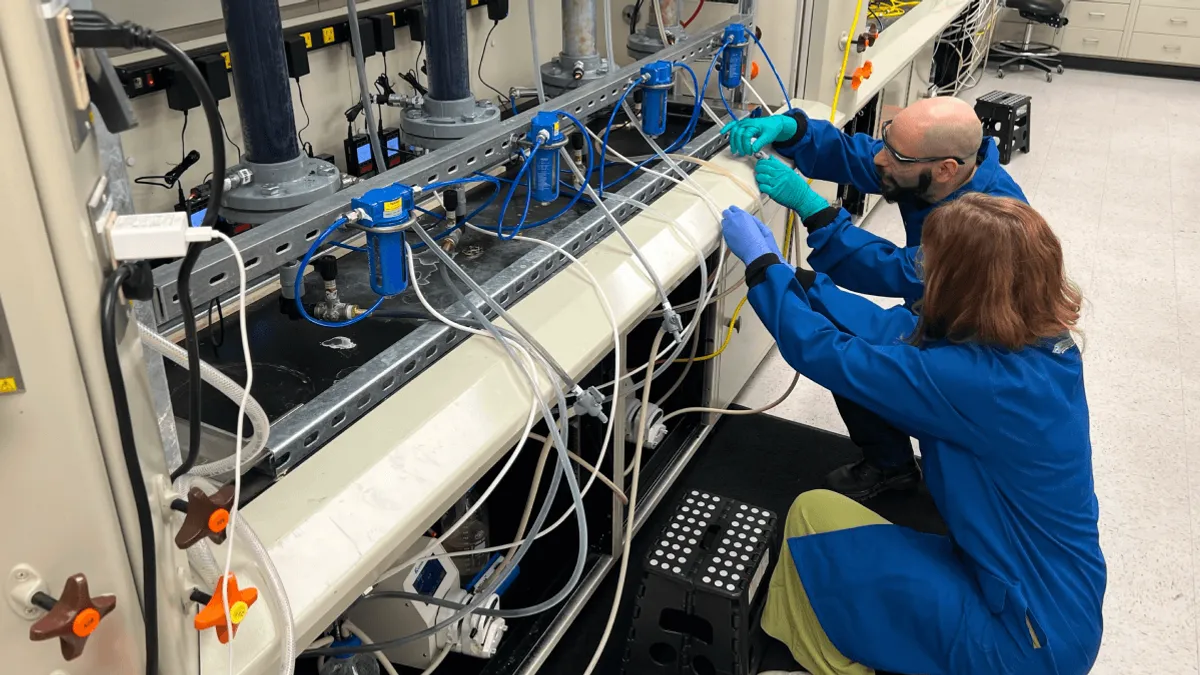

Plus, Andreescu pointed out, many of these products are still in the research phase. Getting them out of the lab and onto products and supply chains in large numbers without increasing costs is a technical challenge. And what works in a lab doesn't always work on the shelves. "I think that's really the question," she said. "Are these technologies ready for large-scale implementation?"

Andreescu's team is looking at developing new packaging that entirely changes color as the food that it contains degrades. It would use printable biocompatible materials with hydrogels that could possibly replace conventional plastics. The biggest challenge is matching the mechanical strength and flexibility of conventional packaging materials because degradable materials aren't very strong, she said.

Recognizing financial concerns, some innovators are trying to make freshness sensors that already work with existing food packaging formats, like Chawang's sensor.

The added costs are one reason many of these sensors are piloted or used on more expensive foods, like meats and seafood. Most of Freshtag’s clients are in seafood and general catering, which includes meal kits and ready-to-eat meals, said Desrosiers. SMU's Chiao said fish is a good potential first use because of its high price.

Veza agreed; she said meat, poultry and dairy are the predominant potential markets for these sensors. "It takes more resources and money to grow and distribute meat and poultry and seafood," she said.

In the longer run, these devices that provide evidence-based data for food freshness could mean cost savings for companies and their retail partners in the form of less waste. "Now they have an intelligent way to manage their supply chain," said Chiao.

But will these types of sensors eventually replace all the date information? "It's going to take time to get regulator confidence to a level to accept that as a new default," Desrosiers said.

And consumers tend to be cautious, said Veza, but "I think that if we can get that trust built, it could really remove a lot of the confusion around date labels and could even replace the date labels."