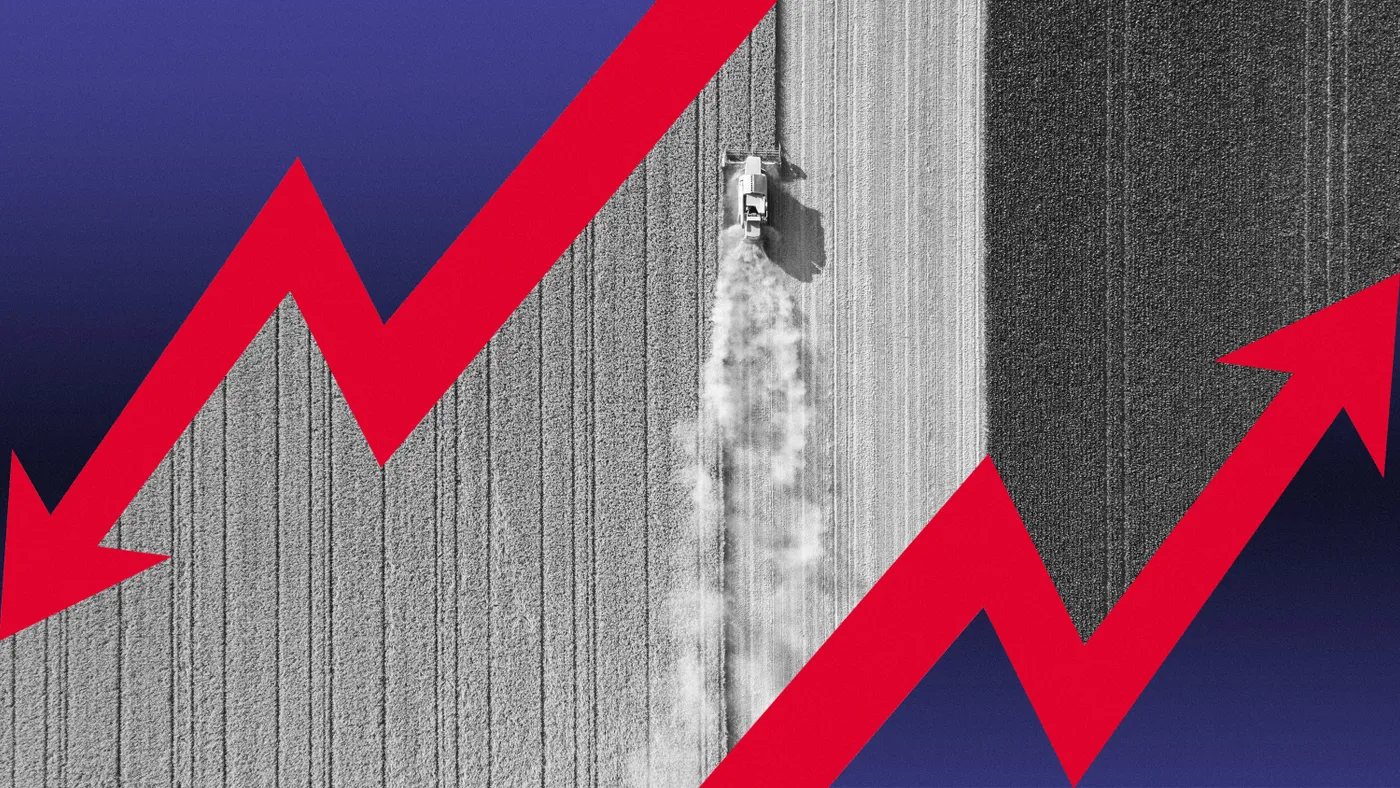

Agriculture is undergoing significant challenges and transformation.

Input costs are rising. Weather and harvest patterns are changing. Sales are declining. The way farmers see it: The old way of doing things isn't working anymore.

In the face of weather issues and market volatility, advanced technologies help farmers maintain profitability in the long-term, but not without upfront costs. Meanwhile, all eyes are on the farm bill as lobbyists push for increased funding for nutrition, crop insurance and climate change mitigation.

Looking ahead to the second half of 2023, the industry is focused on making agriculture sustainable through technology, governmental resources and environment-friendly farming practices — if only it can grin and bear the risks and costs on the horizon.

Regulation: All eyes on 2023 Farm Bill

A substantial rise in projected spending for this year's farm bill has attracted additional political scrutiny, already raising questions on whether lawmakers will be able to reach an agreement before a crucial Sept. 30 deadline.

The budget for the upcoming farm bill could surpass $1 trillion for the first time. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is estimated to make up more than 80% of this year's farm bill, with more than 1 million people expected to enroll in SNAP annually over the next decade.

Congress recently approved additional work requirements to qualify for SNAP as part of an agreement to raise the debt ceiling and prevent the country from defaulting on its loans. But House Leader Kevin McCarthy indicated Republicans could push for further changes, saying "let's get the rest of the work requirements" after the passage of the debt ceiling agreement.

The debate over SNAP injects new uncertainty into negotiations. The current farm bill is set to expire Sept 30, and experts say rules for farm subsidy programs will revert back to 1949 law beginning with dairy at the end of the year.

Beyond the farm bill, agricultural producers are also bracing for fallout from the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that affirmed California's Proposition 12. The law bans the sale of pork, eggs and veal from farms that don't comply with the state's animal-raising production standards.

The Supreme Court ruling could open the door to new state legislation impacting interstate commerce, which farmers say would raise costs of doing business.

Falling prices, rising costs

Lower profits and higher production costs have muddied the outlook for agriculture following two years of strong growth.

Net farm income in 2023 is expected to fall 15.9% from last year's record high, according to a USDA forecast. Although that's still above the 20-year average, profitability is expected to be significantly weighed down by soaring production expenses, falling commodity prices and lower domestic and international demand.

"Market volatility, inflationary pressures and higher expenses, coupled with lower projections for cash crop receipts, are only adding to the stress and uncertainty we face in agricultural production today," Kody Carson, former chairman of the National Sorghum Producers, said at a May Senate hearing.

Production costs soared during the pandemic following supply chain disruption and the war in Ukraine, and expenses are only expected to rise further in 2023. Although some inputs such as feed and fertilizer have seen slight price declines, labor, interest expenses and costs related to livestock and poultry production are all expected to increase this year.

Higher expenses have already taken a bite out of profits, particularly in the meat industry. Soaring prices for live cattle, for example, have compressed margins at industry giants Tyson Foods and JBS Foods.

Crop diversification and risk management

Farmers and ranchers often plan out their harvests months in advance, usually hoping for the best and anticipating the worst. In addition to supply/demand dynamics and weather, their concerns have grown due to recent market shocks, public health scares, financial issues and policy developments.

One way farmers are managing those risks is through crop diversification. Martin Larsen, whose family has been farming in Minnesota for five generations, is a grower of conventional crops like corn and soybeans, but added oats and barley to his operation to improve soil health and spread out his risk.

In a recent testimony, Larsen said diversification and cover crop practices not only improve soil quality, but are “less risky to insurance providers and the federal government that provides subsidies to farmers.”

Other ways farmers can manage their risk is through planting short-season crop varieties that mature earlier in the season to beat the threat of an early frost; installing extra irrigation systems in areas where rainfall is unreliable; or using machines and hired labor to plant and harvest during peak periods, according to USDA’s Economic Research Service. They can also purchase large storage systems for their grain and use marketing, futures or options contracts to hedge price risks.

To offset some of the volatility, agriculture experts and community members are encouraging lawmakers to bolster USDA’s crop insurance safety net for growers in the upcoming farm bill.

Last year, the federal government spent more than $15 billion on the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, created to offset unexpected farm costs. Indemnities — what the government paid out to affected growers — totaled $18 billion and are expected to grow as farming becomes more unpredictable, according to Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget.

Climate change and the return of El Niño

A rapidly changing climate has created a feast-or-famine type production cycle.

Hurricanes, wildfires, droughts and floods battered U.S. farms in 2022, in many cases leading to shortages. But with recent rainfall across the West Coast entering 2023, the situation has reversed for many commodities — an overabundance of supply is now pressuring prices downward.

Global food prices reached a two-year low in May, according to a price index from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The index was pressured by "prospects for ample global supplies" for products such as wheat and corn.

The return of El Niño this year will likely create new challenges for farmers around the world, with drier weather expected "in key cropping areas" such as Central America, Southern Africa and Far East Asia, according to a FAO report.

In the U.S., El Niño will become more pronounced in the fall and winter, bringing the potential for wetter-than-average conditions in Southern California and along the Gulf Coast. Drier conditions are expected in the Pacific Northwest and Ohio Valley, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said.

James O’Rourke, director and CEO of fertilizer input producer Mosaic, said on a May earnings call that El Niño is already beginning to negatively impact grains and oilseeds.

"It would take two to three years of perfect weather and adequate fertilizer applications in every major growing region around the world just to get back to normal levels," O’Rourke said. "With weather patterns shifting to an El Niño environment, the likelihood of that happening is low."

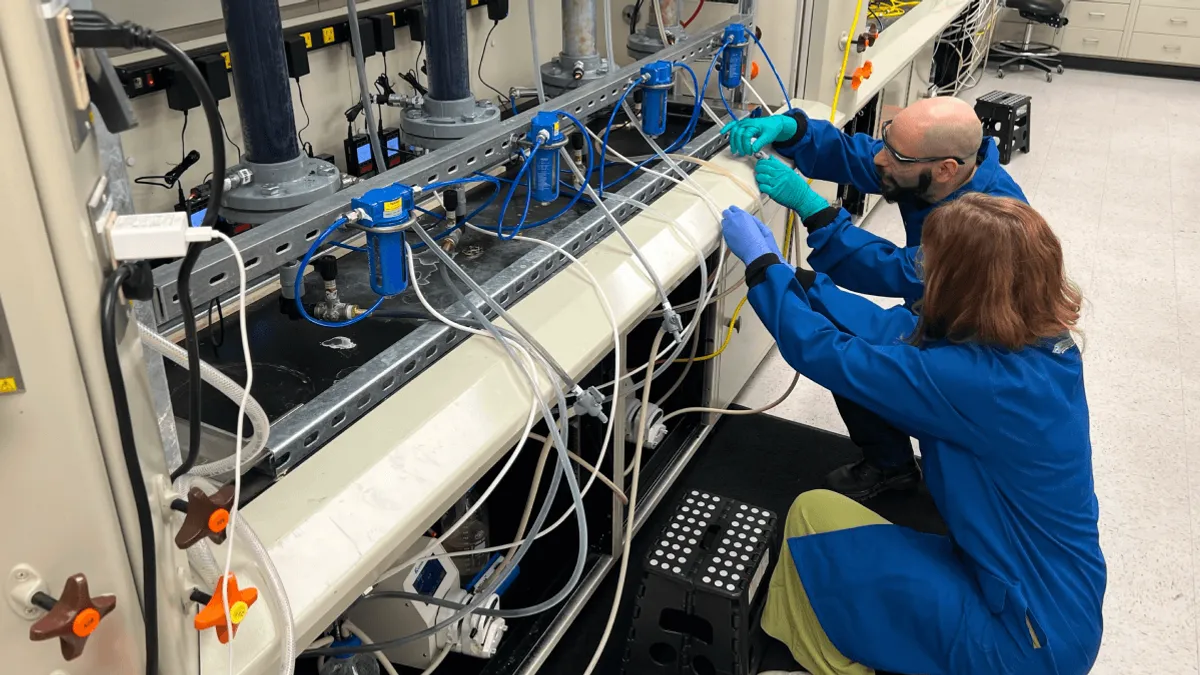

Precision agriculture on the rise despite costs

With the advancement of technology, farming has evolved and efficiencies have increased, allowing farmers to do more with less. One of the latest advancements popular among crop growers is precision agriculture, a practice where farmers use a mix of technologies to measure and manage segments of their fields in real-time.

Bret Johnson, a fifth generation farmer and president of the Iowa Farm Bureau, testified this month at a Senate committee hearing about the benefits of precision agriculture on his land, saying “it’s become a necessity.”

As farmers take on more risks related to climate or finances, he said the ability to measure and manage which parts of the field are doing better than others, and ultimately where fewer money, time and resources are needed, allows him to better manage his risk.

“It’s allowed me to increase my yields while reducing my inputs so my efficiency numbers have actually been growing,” Johnson said at the hearing.

In general, about 1.2 pounds of nitrogen is required to produce a bushel of corn, according to Louisiana State University’s College of Agriculture. However, Johnson said through precision agriculture, he has found parts of his field that require significantly less nitrogen: as little as half a pound per bushel.

In addition to input management, precision agriculture tools have the potential to identify and address plant and insect diseases through field mapping software and other technologies that measure crop, soil, air and weather conditions.

Despite cost savings, adoption rates have varied among farmers. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, one of the main hurdles is adjustment costs related to subscription fees, training, maintenance and equipment costs. Yield monitors, guidance systems, drones and variable rate technologies can cost tens of thousands of dollars to implement and replace.

On average, the cost of a yield monitor replacement for soybeans was more than $8,000, in addition to an annual $1,000 fee, according to data from a survey of farmers in 2018. Guidance system replacements surpassed $20,000. Meanwhile, drones typically cost about $2,000 pre-owned.

But for early adopters, precision agriculture is essential. Johnson said it “plays a huge impact into risk mitigation and my ability to do my job even better next year.”