Farming has become an extremely precarious business. Without many previously critical subsidies, margins have become slimmer or nonexistent. Climate change has made drought and flooding more common, threatening several crop harvests. And a globalized economy has created regional conflicts that cause widespread impacts on costs and supply.

As agriculture transforms and farmers change the way they work, the struggle to adapt to this rapidly changing climate is being felt far and wide.

“We’re an intergenerational farm,” said Harold Wilken, a fourth-generation grain farmer located outside of Chicago. “When I was a conventional farmer, the margins were so small, and I knew there was no way that my son or my nephew could farm with me. By moving away from conventional methods, it gave us the opportunity to have more income to bring in the next generation.”

Rebecca Chesney, a food anthropologist and the director of sustainability innovation at ISS Guckenheimer, a corporate catering food service company, identifies three core paradigm shifts currently occurring in agriculture and how some farms are dealing with the changes.

1. A move away from yield and revenue to a profitability and input costs focus

Between 1965 and 2019, farmer yields increased by 44%, primarily due to the Green Revolution, which introduced the widespread use of fertilizers, pesticides and high-yield crop varieties. For farmers selling their crops to aggregators who combine a single crop type from various suppliers — known as commodity or elevator farmers — the sole method to boost profits was to increase revenue by increasing yield.

“That was really the focus,” Chesney said. “Just grow more, sell more and bring in more. It became a singular focus on finding these high-yield crop varieties.”

Agriculture became an intellectual property game. Companies that had patents on the seeds and inputs that produced the biggest plants, thrived. Between 2018 and 2020, just three companies — Bayer, Corteva and Syngenta — accounted for more than 70% of the seed sales for corn and soybeans.

The consolidation of suppliers, combined with a globalized food system that is highly sensitive to supply chain disruptions, has led to an increase in input costs. The war in Ukraine forced fertilizer prices to increase between 27% to 53% over the first five months of 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Since 2020 the total costs paid by farmers and ranchers to raise crops and livestock has increased 28% or close to $100 billion.

“There’s another way to think about profitability,” Chesney said. “Reducing your costs. That’s really what the shift is. People are still talking about yield, but they’re also talking about costs.”

Todd Barkley, a fourth-generation farmer in Montana is focusing on enhancing his farm’s native environment and soil so he can cut the costs associated with chemical fertilizers, and as a bonus decrease the farm’s carbon footprint.

“We went from trying to get maximum production out of the cow to trying to get the maximum production out of our property,” he said. “We were able to increase the production of our ranch and decrease the actual inputs into the cattle. Same with our cropland.”

Barkley has seen an increased carrying capacity on his ranch by 60% while applying half as much fertilizer.

2. A shift from soil chemistry to soil biology

The Green Revolution put a heavy emphasis on three key soil minerals: nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium — chemicals that could be replenished via fertilizers. These fertilizers were magicians when it came to producing more food per acre. But reliance on them not only increased farmers’ costs, it also degraded soil quality, polluted waterways and the production and degradation of these fertilizers releases carbon dioxide.

“We actually need to look at soil as the living thing that it is and support it as a way of helping the farm,” Chesney said.

In the past decade, the study of soil science has significantly increased in both quantity and influence. The number of journal articles on the subject has dramatically increased and influenced change.

Farmers are now focused on the biological processes of their soils. Mycorrhizal fungi, which live symbiotically on plant roots, and the amount of organic carbon in soil have received much more attention.

Another big driver for having healthy, biologically active soil is water. Water has become a scarce, unpredictable and sometimes expensive resource for farmers looking to avoid dry, damaged soil. Comparatively, healthy soil has much better rates of water infiltration, in which it acts like a sponge holding onto rain or irrigation water.

Farmers want healthy soil, not just soil with the right ratio of chemicals.

“I wanted to get away from the chemicals and the petro fertilizers and go back to more natural methods,” Wilken said. “Now, I like to call our soil chocolate cake. It’s crumbly and it has lots of organic matter, fungi, protozoans and bugs.”

3. Uniformity to diversity of crops

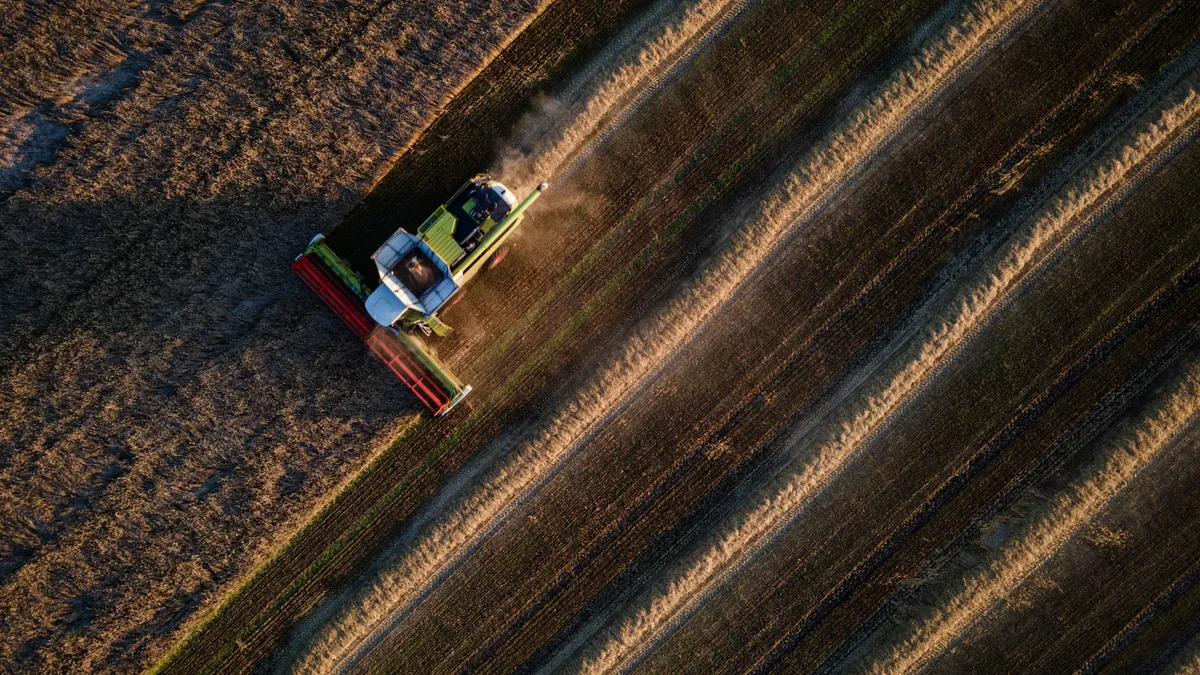

In the late 20th century, farming followed a factory model: perfecting the growth of a single crop and repeating the same process annually. Planting the same crop in the same soil made it easier for farmers to use machines, and sped up seeding and harvesting. However, despite this efficiency, the environmental impacts degraded the soil, sometimes to the point where nothing could grow.

Recently, farmers have taken up crop rotation and cover cropping to introduce more diversity. Barkley transformed some of his less productive cropland back into grassland and uses up to 16 different seeds in his cover crop as well as growing safflower and flax when seeding his spring wheat.

There is also new interest in less mainstream crops like fonio (even Bill Gates is on board) so farmers have more crop options to grow.

The consolidation of agriculture companies has also led farmers to grow identical plants from the same identical seeds bought from a few conglomerates. On the consumer side, right now 50% of calories come from just three crops — rice, wheat and corn.

While previously there might have been some varietal diversification in those three popular grains, the focus on high-yield commercial varieties has stamped out the local indigenous ones. According to a study from India, the country’s local varieties of rice have decreased to 7,000 from 100,000 in the 1970s.

“Now because of climate change, we're realizing we might need more drought tolerant varieties or varieties that can grow in poor soils or are resistant to pests and fungal diseases,” Chesney said. “But a lot of the wild varieties holding those genetic traits are on the verge of extinction.”

Momentum behind these mindset shifts comes from big consumer packaged goods companies that are reliant on one or a handful of specific crops currently experiencing historic declines. What is Starbucks without coffee? What is Nestlé without cacao? These companies are desperate to find solutions to this existential threat to their businesses and changing these ingrained models of thinking might be the first step.